Support Northern Colorado Journalism

Show your support for North Forty News by helping us produce more content. It's a kind and simple gesture that will help us continue to bring more content to you.

BONUS - Donors get a link in their receipt to sign up for our once-per-week instant text messaging alert. Get your e-copy of North Forty News the moment it is released!

Click to Donate

By Theresa Rose, North Forty News

For those seeking authenticity in Western American music, they’ll find it in Gary McMahan. He is as much a cowboy as a man can be, having spent the first 20 years of his life on the back of a horse. In the ’50s and ’60s he could ride, rope and brand with the best of the old timers, working for the Orr Cattle Company in Greeley. He rodeoed, of course. His father owned a fleet of 50 trucks and moved cattle under the name of Livestock Transport Inc. McMahan could have been part of the family business after high school but, he said, he “couldn’t see the point in that.”

Gary McMahan had always been an entertainer, the “class clown” as he puts it. He looks back on his high school years as a “great time” when he had a rock band and performed in school plays. But the real arrowhead that pointed to a future as a performer was winning first place in the state speech championship. He memorized a poem called “Croppie the Cowhorse” (author unknown), a tearjerker of a story about the love between a cowboy and his horse, in which the heartbroken cowboy is forced to shoot his beloved companion after the animal breaks his leg. The recitation was an astounding success and the start of what would become his career. He said he began writing songs “just for the Hell of it.”

He joined the navy from 1968 to ’71 during the Vietnam years as a medic, where he was stationed on the East Coast. His job was to patch up “planeloads and planeloads of blown-up guys.”

“If folks today think the world is falling apart, they should have seen it then,” McMahan said.

After his stint with the Navy, he decided Nashville was the only place to go, “where the guy pumping your gas could write a better song than you could. But that’s where you learn how to write.” He also discovered that the only people writing cowboy songs were himself, Ian Tyson and Chris LeDoux. LeDoux, like McMahan, also was a real cowboy who rode, roped and rodeoed before breaking into country music. He and Tyson began recording McMahan’s songs at that time, as did the Starlight Ramblers.

He was signed on by Tomato Records, who also managed the legendary songwriter, Townes Van Zandt. In 1978, Tomato released Colorado Blue, McMahan’s first record. All this time, he’d been honing a peculiar skill — yodeling — inspired by Montana Slim, a Canadian yodeler from the 1930s and the simple yodels of Jimmy Rogers.

“It is an art form and you really have to work at it,” McMahan said. The skill “totally bypasses the brain and is rooted in the emotions.” With the advice of Baxter Black, a cowboy storyteller who advised him to “put on a show,” he began to perform a stage act combining humor, music, yodeling and poetry. He says his stories must be based on reality, “because you can’t make this stuff up,” and he tells others’ stories as well as his own.

Tomato Records went broke and he wound up on a dude ranch in Aspen driving a stagecoach. Yodeling became a sales tool, a unique method of attracting customers on a job that lasted from the late ’70s to 1985. Many in the Fort Collins area remember McMahan from the Double Diamond Stable at Lory State Park in 1985. He ran the stable until about 1989, when the Western Music Association, begun by Bill Wiley, who had managed the Sons of the Pioneers in their heyday, decided to hold a yodeling contest in Tucson to promote his new business. Riders in the Sky were getting to be big at the time and performing a lot of McMahan’s material, bring even more attention to the yodeling contest. McMahan won the contest. He’d been yodeling every night for years by then. He quit the music business, saying, “If you’ve got half a brain cell left, you never want to go into the music business,” citing the plethora of exploitation and dirty deals rampant in the industry. His venues tend to cater to the agricultural industry: county fairs, grower’s and livestock associations and similar gatherings where he said “the checks don’t bounce.”

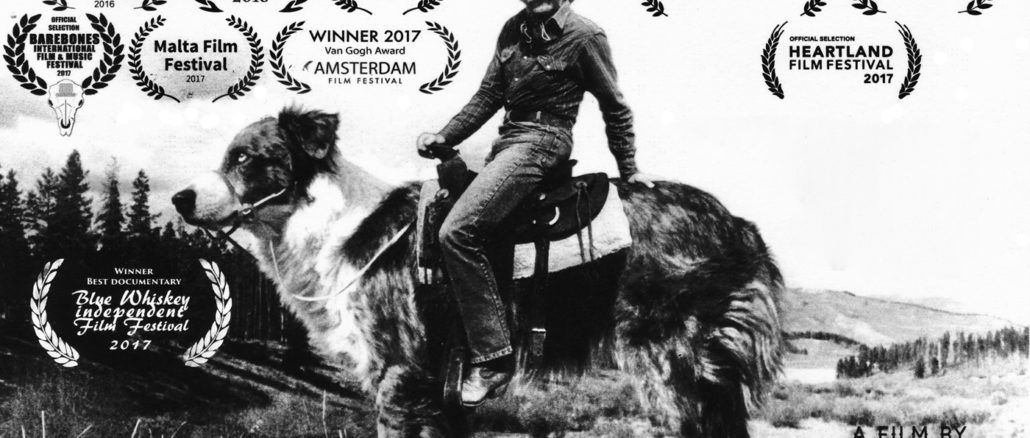

He attracted the attention of Doug Morrione, a media professional and owner of Matador Productions and Main Street Media, who wanted to make a documentary focused on McMahan. But MacMahon had other ideas and insisted on an unscripted film about himself and a few friends of his, Jeff Nourse, a cowboy and master welder, and Yvonne Hollenbeck, award-winning quilter poem, “What Would Martha Do?” is a smug take down of the famous home-making queen in the face of the challenges of a ranch wife.

Everything in the Song is True is an award-winning film, including the award for Best Film at the Chicago Film Festival and the Amsterdam Award for Cinematography. But McMahan is not one to sit still very long.

“At this point in time, I can do this better than I ever have,” he said. “I’m allowing myself to enjoy this.”