Bio Bites

By R. Gary Raham

A biologist-artist’s ruminations about our roles in a science-inspired world

After the snowstorm is over, and the sun comes out again, take a walk in the woods to relax. While much of nature lies dormant, some critters stay active—like tiny pioneers of the soil called snow fleas. Check out mounds of snow near trees or weedy stems. If you see a pattern of tiny dark flecks against the snow’s fluffy whiteness—about the same size as grains of pepper—you may have found a population of snow fleas or springtails.

Springtails are primitive arthropods—kind of ur-insects, if you will—that were some of the first colonizers of dry land. They live modest lives in the leaf litter all year round until their population numbers explode—often in the winter when some of their predators, like ants, are resting in their tunnels—and then they blunder up through holes in the snow to frolic.

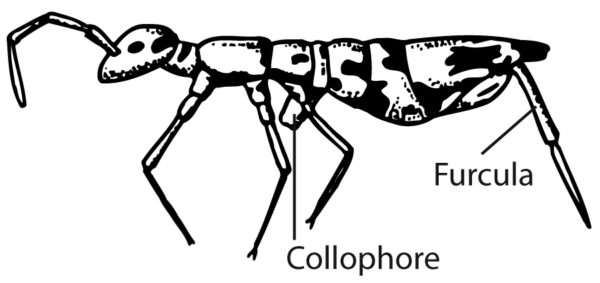

These critters get their name from a unique organ on their abdomen called a furcula that allows them to hop around like tiny kangaroos—or energetic fleas. Think of the furcula as the pin part of a safety pin, but with two prongs on the end. A pair of clasps on the third abdominal segment holds the prongs in place. When the clasps release the furcula, it springs open to shoot the springtail up to 4-6 inches into the air. If humans like you or I had such a propulsion system we could hop the length of one-and-three-quarter football fields.

An Englishman who first studied these creatures noticed that they possessed a short, peg-like tube on their belly. This soda straw-like organ, the collophore, allows springtails to slurp water from the soil and from plant tissues. They can also use their forelegs to groom their bodies with collophore liquid, much like your cat does with a lick and a paw.

For the most part, springtails mind their own business breaking down plant material into humus, eating soil fungi and nematodes, and tidying up the droppings of other animals. They come in an assortment of colors, shapes, and sizes that varies somewhat with soil depth. As many as a quarter billion springtails may roam in one acre of soil. They don’t bite, and are not often pests, except sometimes in mushroom farms and tree nurseries. Springtails can live on alpine mountaintops and get storm-tossed up to two miles high in the atmosphere.

Springtails live in a dangerous world where spiders, mites, and assorted other arthropods always appreciate a hopping good meal. Springtails can defend themselves with toxic chemicals. At least one kind of ant specializes in munching springtails with special spring-loaded jaws that snap shut when a springtail trips special sensory hairs on the ant’s mandibles.

Much springtail biology remains a mystery, a fact that is a little surprising considering their abundance, but they do keep a low profile. If you need a little project to keep yourself amused during a sequence of snow days, hunting springtails might be just the thing. No, you wouldn’t be weird—but you might be a budding naturalist!

Support Northern Colorado Journalism

Show your support for North Forty News by helping us produce more content. It's a kind and simple gesture that will help us continue to bring more content to you.

BONUS - Donors get a link in their receipt to sign up for our once-per-week instant text messaging alert. Get your e-copy of North Forty News the moment it is released!

Click to Donate